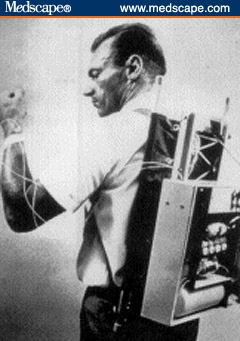

One exciting new piece of technology available to people with diabetes is the insulin pump. This has certainly evolved by leaps and bounds from its original prototypes (picture from medscape.com) to the newer devices.

One exciting new piece of technology available to people with diabetes is the insulin pump. This has certainly evolved by leaps and bounds from its original prototypes (picture from medscape.com) to the newer devices.

However, as exciting as this may be, the pump requires vital input from the patients. The current ones are not yet closed-loop, autonomous devices. Patients still need to have the ability to count their carbs, and need at least 3-4 blood glucose checks a day. It is a terribly common misconception that the pump is completely automatic and one doesn't need to do anything. That this will magically control their diabetes. In addition, the pumps are expensive and generate multimillions of dollars for the manufacturers. So, I'm particularly selective about the patients I put on the pump and I don't usually recommend this for many patients. The studies have clearly shown, if noncompliance is an issue, getting the pump will only worsen the diabetes.

Unfortunately, methinks because of kickbacks (clinics get paid for every pump they put on), I see more and more patients on pumps, whether or not they are suitable candidates. Patients who have no clue how to count carbs. Or check their sugars once a week. Or have no idea how to operate the device. And amazing as this may sound, some claim they were started not by a diabetes specialist, not even by their GP, but at certain pharmacies in the state (rumor has it that the pharmacy is getting an off-site doctor to write the prescription without even seeing the patients)!

Now the pump is meant to be a personal insulin delivery device, one that the patient manages under the guidance of a practitioner. This is not meant to be managed by nurses or doctors caring for the patient. So, good understanding is vital. It's like driving a car- you need to know how to operate your own car. The problem I've seen more and more of late, are patients admitted to the hospital for other reasons, on insulin pumps. Except some I've struggled with of late have no clue how to operate their devices, or count carbs, and when they get hypoglycemic in the middle of the night, don't know how to decrease the basal rates, or suspend their devices. It gets frustrating to see a patient on consult and to ask the patient for his/her rates but only for them to shrug and say they have no clue, and don't know how to pull it up from their machine. And so this gets dangerous, as even the nurses and other doctors are not trained to manage a person's personal insulin pump device.

And so, maybe I'm just slow to adopt new technologies, but the pump is something I'd offer to my motivated patients who are wanting to find some flexibility in their insulin programs, who are open to learning and are committed to regular glucose monitoring. These patients tend to do well with the pump. However, I tell them that most studies don't show an big improvement in hemoglobin A1c with the pump; the main benefit is that it makes life a bit more convenient for them. But for the others, the ones who forget to take their insulin, or refuse to self-test, or cannot count their mealtime carbs, I tend to discourage them from getting the pump.

<< Home